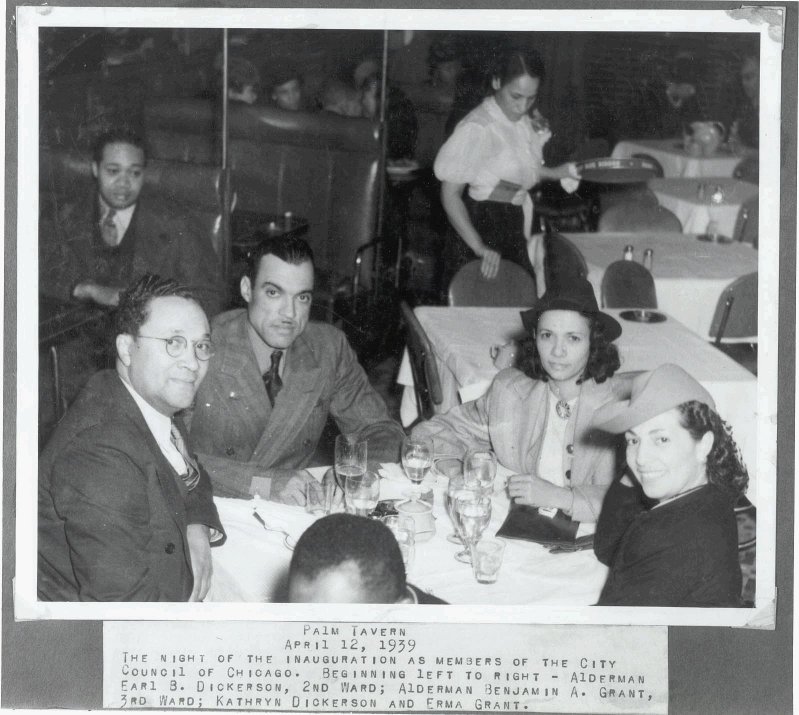

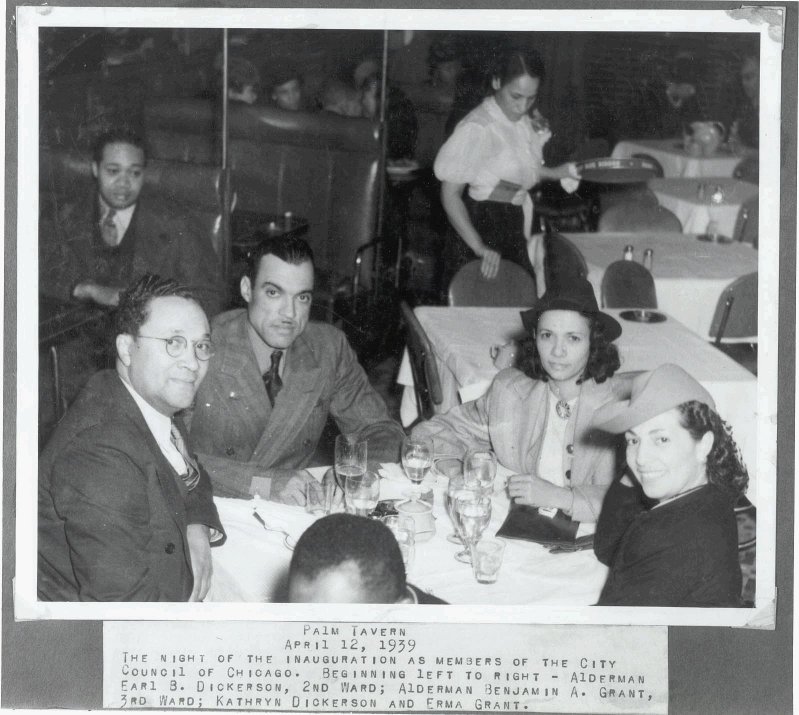

Earl B. Dickerson at the Palm Tavern

Attorney Earl B. Dickerson Fights Restrictive Covenants in Washington Park

The Lee v. Hansberry, United States Supreme Court, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) case decided a relatively narrow issue of constitutional law that is unrelated to the ultimate issue of restrictive covenants, but the case is remembered because it was a significant legal battle, defended by Earl B. Dickerson and financed by the Supreme Liberty Life Company. Dickerson's success in Lee resulted in the opening of housing in Chicago neighborhoods that previously were about 80% protected by Restrictive Covenants.

The Lee case is summarized in the law review article "Rethinking the "Day in Court" Ideal and Nonparty Preclusion" by Robert G. Bone , 67 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 193, 215

Conventional wisdom has it that Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) constitutionalized interest representation by holding that adequate representation of interests can satisfy due process requirements for binding an absentee to a judgment. The Court's opinion is far from clear on this point, however. Although the Court employed the language of "interest representation," it stopped short of fully endorsing an interest representation theory.

Hansberry v. Lee was decided before Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), which held that racially restrictive covenants were unconstitutional. Hansberry involved an attempt to enforce one such covenant in a Chicago residential neighborhood. The previous lawsuit, Burke v. Kleiman, 277 Ill. App. 519 (1934), was a similar enforcement action brought on behalf of the plaintiff and "other property owners in like situation." Hansberry, 311 U.S. at 39. By its terms, the covenant was to be effective only if ninety-five percent of the lot owners signed it, and all the parties in Burke stipulated that this condition had been satisfied. In Hansberry, the defendants sought to challenge the covenant on the ground that the requisite number of signatures had not in fact been obtained. The Illinois trial court held that the defendants were collaterally estopped from arguing this point by virtue of the judgment in Burke v. Kleiman. The Illinois Supreme Court affirmed, Lee v. Hansberry, 24 N.E.2d 37, (1939), but the United States Supreme Court reversed, holding that the application of collateral estoppel violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Hansberry, 311 U.S. at 44-45. For an engaging account of the history of Hansberry v. Lee, noting that the Hansberry family was the same as the one depicted in Lorraine Hansberry's "A Raisin in the Sun," see Allen R. Kamp, The History Behind Hansberry v. Lee, 20 UC Davis L. Rev. 481 (1987).