Bar Fight

Chicago Says Last Call, but the Palm Tavern's Owner Is Good for Another Round

By Teresa Wiltz

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, May 29, 2001; Page C01

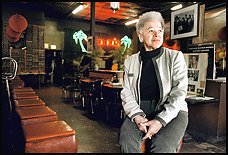

Gerri Oliver has run the Palm Tavern,

a landmark in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood, for 45 years.

Now she's fighting the city to keep it open.

(Jerome De Perlinghi - for The Washington Post)

CHICAGO IT'S ONE OF THOSE GRIM DAYS ON 47th Street, a day that makes the grit stand out amid the gray. Cold. Weary. Sad. Past the boarded-up buildings, past the liquor stores where Mad Dog is peddled behind bulletproof partitions, past the African hair braiding salons -- and past the new construction that brings with it new money -- a splash of bright red creeps down the street. The color is sassy; the lady wearing it anything but. Age hunches her shoulders, beating them down until they cave somewhere around her heart. "You see that woman over there?" says Geraldine "Mama Gerri" Oliver, proprietor of the once-famous Gerri's Palm Tavern in the Bronzeville neighborhood. "That was the queen of 47th Street at one time. You see what not taking care of your bones will do? That's enough to make me want to cry, seeing her walk like that, when she used to walk so proud down the street at one time." If the woman in red was once the queen of 47th Street, then Gerri's Palm Tavern was the undisputed belle of this once-bustling South Side strip. Langston Hughes sat scribbling at the bar, while members of the black glitterati -- Lena Horne, Duke Ellington, Josephine Baker -- dropped by to chill out. In 1933, the Chicago Defender, then the nation's leading African American newspaper, dubbed the Palm Tavern "the most high-classed Negro establishment in America." And so it was. Once. Like the old woman, the Palm's bones haven't held up too well. Its roof is caving in. Time cracks the leather booths. Dust kisses the bottles lined up against the bar. Mama Gerri, who has run the tavern since 1956,has been sleeping on an old mattress laid on the floor of the Palm's decrepit kitchen. Now she's being moved out, her saloon in danger of being shuttered to make way for change. Today, in an eminent-domain case, a Cook County judge will decide if the Palm Tavern should be turned over to the city. This is redevelopment at its most ambitious, a plan overseen by Alderman Dorothy Tillman, whose ward includes Bronzeville. A plan that entails turning 47th Street into the city's official "Blues District," an entertainment destination for tourists seeking out spanking new blues clubs, a Second City comedy franchise, restaurants, an "African bazaar," a park dedicated to Quincy Jones and a sprawling cultural center named after native son Lou Rawls. She's dubbed the street "Tobacco Road," after Rawls' hit. Progress. Progress flush with city funding and developer's cash. Progress that pits two strong-willed women, former allies, Oliver and Alderman Tillman, against each other in a battle to control the legacy of Bronzeville. "It doesn't look to me like this ought to be World War III," says U.S. Rep. Danny Davis, a Democrat whose district includes Bronzeville. "Sometimes these things can take on a great deal of emotion. And before you know it, what should have been a small disagreement becomes a major issue requiring international diplomacy." A Festering Feud Those watching from the sidelines shake their heads, perplexed over how it has come to this. It's a convoluted tale, to be sure, one that involves Chicago-style politics, development deals, two court cases, gentrification and a lot of history. But at its essence, this is about two women. Two black women, that is, and one very dilapidated 35-foot storefront that houses a historic black establishment. There's Oliver, nearly 82, the daughter of landowners, short, pale, feisty, sharp-tongued and stubborn. She's been a Chicago resident since the early '40s, part of that first wave of migrants heading up from the South in search of the good life. And then there's Tillman, 54, the daughter of laborers, tall, dark, equally feisty, sharp-tongued and stubborn. She first came to Chicago in the late '60s as a civil rights activist, left, and then came back, part of the second wave of migrants heading up from the South in search of the good life. The two women haven't spoken in several years, but once they were, if not friends, friendly. Each claims that, at one point in time, she saved the other from impending disaster. Suffice it to say that now it's not likely either one would return the favor. Oliver owns her business but not her building. This fact will be crucial in determining her fate: The city slapped the edifice with numerous building code violations. And last week, her landlord, David Gray, handed her an order to vacate. (Gray, who purchased the building for $8,000 in a tax sale, did not return phone calls requesting comment.) For now, she's worked out a deal with the city, one that provides her with an apartment and allows her to continue to run her business. For now. The city is trying to buy the building. As alderman, Tillman has a good deal of say-so over what happens in her district of 60,000, which encompasses some of the city's most blighted stretches, including two giant public housing projects. When asked about renovating the Palm Tavern to preserve its history, Tillman says, "Why would I want to do that?" History Out, Money In That is a question that isn't confined to the borders of Bronzeville. Indeed, this sort of gentrification drama is being played out around the country, from Oakland to Kansas City to Harlem to the District of Columbia. In Harlem, mom-and-pop shops lining 125th Street have been nudged out; in their stead are mega-retailers like Disney, Old Navy and Starbucks. Those seeking a little history with their lattes can take guided tours to the Theresa Hotel and the Audubon Ballroom, where Malcolm X was assassinated, or pay $30 to visit a gospel church. And in Washington, along the U Street corridor, once the District's Black Broadway, clubs and theaters like Bohemian Caverns and the Lincoln Theatre have been preserved. But there are fears that other, less visible pieces of history, like the Seafarer's Yacht Club, the first African American boating club on the East Coast, will lose out as development creeps along the Anacostia River. No one questions the need to pump fresh blood into atrophied neighborhoods, nor is gentrification anything new. But the current spate of renovation poses a troubling question: What parts of history get preserved and what parts get bulldozed in the name of progress? And just who gets to decide what constitutes progress? "Developers are making money from marketing the Jim Crow segregation," says gentrification researcher Brett Williams, chairwoman of the anthropology department at American University. "But real living black communities get demolished and living people get displaced, while there's this selling of the old ways. It's tourism for the middle class and elite people who want to live in or visit a place they think has charm and character but not too much of it. "Where are the poor people supposed to go?" Others point out that history is best preserved when there is tangible proof that it actually existed. "One thing you can do if you want to destroy a people's history is to destroy the physical part," says Timuel Black, a Chicago historian, community activist and Bronzeville native. "Then it's too hard; you have to stretch the imagination too much for later generations. What if you destroy the Colosseum in Rome or the Parthenon? Not that I'm comparing the two to the Palm Tavern. But those two were preserved purposefully to retain the history of the people who came before. "The Palm Tavern is a memorial to the struggles of black people of the past. And the successes. Heck, you could go into the Palm Tavern anytime and see men who had money beyond what we thought black people could have." The Other Main Street Scroll back a few decades, to the time of the Great Migration, when hundreds of thousands of African Americans bolted the brutality of the rural South for the urban, just-as-brutal North. Restrictive housing covenants kept them out of the rest of Chicago, so they flocked south of the downtown Loop to Bronzeville, also known as the Black Metropolis. Business -- and life -- thrived. In 1945, St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, writing in "Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City," had this to say of Bronzeville's commercial strip: "This is Bronzeville's central shopping district, where rents are highest and Negro merchants compete fiercely with whites for the choicest commercial spots. A few steps away from the intersection is the 'largest Negro-owned department store in America.' A few doors away, behind the Venetian blinds of a well appointed tavern, the 'big shots' of the sporting world crowd the bar on one side of the house, while the respectable 'elite' takes its beers and 'sizzling steaks' in the booths on the other side." That "well appointed tavern" was the Palm, opened in 1933 by James "Genial Jim" Knight, the "first mayor of Bronzeville," a former Pullman porter turned businessman and "Policy King" -- that is to say, a numbers runner. The Palm Tavern quickly became the place in which to gawk and be gawked at. Oliver, who came to Chicago to be a mortician but ended up a manicurist, met Knight while doing his nails. In 1956 he sold her the business. "Back then, everybody knew everyone, everyone was cordial to everyone," she remembers. "You were treated like a lady, and the gentlemen were always there to protect your back. It was a beautiful era back then." At the Palm, there was Langston Hughes, noshing on red beans and rice as he crafted columns for the Chicago Defender. Joe Louis courting his bride. Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Lena Horne, coming in to cool down between hot sets at the nearby Regal Theater. Youngsters like Timuel Black who were not old enough to enter the Palm, stood outside, watching the glamorous parade: Billy Eckstine, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Quincy Jones, Flip Wilson. Josephine Baker posed for pictures with Oliver. Later, there was Jesse Jackson, working out the details of Operation Breadbasket. Much later, Harold Washington celebrated his first mayoral victory there in 1983. But by then the jobs in Bronzeville had evaporated. Those who could move out, already had. Drugs and gangs moved in. As Oliver was learning how to be a saloonkeeper, Tillman was a 9-year-old in Montgomery, Ala., learning firsthand the political value of walking instead of riding in the back of the bus. At a very early age, Tillman became mesmerized by Martin Luther King Jr. and his message. So much so that she became a teenage activist working for him at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference -- a position that brought her to Chicago in 1965. She later moved to San Francisco, but soon returned. Chicago had honed her appetite for activism and, in 1983, after more than a decade of agitating for school reform, she took office in the Third Ward. As Tillman's political career began to flourish, Oliver was experiencing a downturn. She and her cats moved into the Palm, partly because, Oliver says, she was swindled out of her apartment and partly because she wanted to protect her business. (Her son, two grandchildren and three great-grandchildren all live on the West Coast.) Until last week, clothes on hangers swung from the hooks next to the leather booths. Her Buddhist shrine sat parked on one of the tables. This is all she has known for nearly five decades. Some say it's way past time for her to move on. Says Chicago real estate developer Dempsey Travis: "Unfortunately, Gerri hasn't recognized that life has gone on. She's not going to be able to raise the kind of capital to make [the Palm] what it should be. I know nobody wants to hear me say that, but it's true. "She's sleeping on the floor in the old kitchen. That tells me it wasn't very good to her. The people that I knew who were the owners of that establishment back in those days lived like kings. . . . You have to recognize when it's time to step aside and let younger minds and younger bodies into the forefront." Indeed, today, they don't pack 'em in like they used to. Still, folks stop by for a friendly drink. And every weekend, the play "I Was There When the Blues Was Red Hot" runs at the Palm. Admission is $10. To gain entrance, you have to be buzzed in. Taking It Back There are signs of change in Bronzeville. The housing projects are being torn down; it's not clear where the residents will go. A recent "parade of homes" showcased new construction by African American architects; banners along once-beautiful Martin Luther King Jr. Drive advertise new condos -- "starting at $85,900" -- but home buyers insist nothing can be found for less than $250,000. Despite the apparent growth, construction on the Lou Rawls Cultural Center, which will feature a theater and a restaurant, has been stalled. Just wait, Tillman says. In two years you won't recognize Bronzeville. "This block was nothing but drugs," she says. "They told me, 'It's not going to come back.' It was going to come back. Because I have faith in my people. . . . You know you're going to win. You have a resolve. And we have a very strong resolve." This resolve means she's not above laying down the law, "Tillman's law," as she puts it: Putting claims on vacant lots to shoo away would-be developers that she deems unworthy of investing in her neighborhood. Insisting that any developer breaking ground in Bronzeville has to employ a crew that's 70 percent African American. Her detractors call her a demagogue, a one-time activist who made a deal with Mayor Richard M. Daley and turned her back on her values. In her activist zeal, she brings to mind the Rev. Al Sharpton. If, that is, Sharpton had a penchant for silver running shoes and church-lady hats. She's fast-walking, fast-talking. Doesn't shake hands so much as crunch them. She knows what she wants, and doesn't take kindly to being questioned too closely by strangers. She starts quoting the Bible and muttering about media manipulation -- just before she abruptly ends the conversation. She's particularly irritated when asked about the Palm Tavern. "Let me tell you something: The [Chicago Tribune] did a front-page story on poor, little Gerri. . . . Gerri's not a poor, little person. Gerri's in that building on her own." This is where things get murky. Tillman says she's offered Oliver "fair market value" for the Palm Tavern. The city, however, has yet to purchase the building. She says that when Oliver was burdened with an overdue $34,000 water bill, it was she who negotiated with the city on Oliver's behalf, saving her from certain eviction. Gary Fresen, Oliver's lawyer, said Tillman did nothing of the sort; it was he who helped Oliver straighten things out. Oliver will tell you that it was she who helped Tillman over the years, not the other way around. Helped her find a babysitter for her five kids. Hired her now-ex-husband, a blues-jazz musician, to perform at the club. Told her where to buy those hats. "You don't look for someone you're helping to turn around and put a knife in your back," Oliver says of Tillman. It's hard to say where things went wrong between the two women. Publicly, Oliver will say she doesn't want to see "two black women get involved in [expletive]. Because you see the white man is controlling all this." And then she covers the tape recorder and indulges in a little character assassination. Off the record, of course. A Building of Dreams What will happen from here is anyone's guess. Oliver's supporters are circulating a letter to Mayor Daley. The city has found her a new apartment near the Palm, will advance her $3,000 toward living expenses and has assigned 24-hour security to guard the tavern. So far, no one has come forward, offering to invest in the Palm. Developer Elzie Higginbottom, who razed the Regal Theater 30 years ago and is now developing some of the 47th Street projects, says that renovating the restaurant would require a total "gut job." According to Higginbottom, that would take hundreds of thousands of dollars. If the city succeeds in its bid to buy the Palm, it will see if the building can be used for "entertainment purposes," according to Becky Carroll, communications director in the city's planning department. Whether the Palm will remain the Palm is "open for speculation," Carroll says. The city will solicit proposals from possible investors. The city could buy Oliver's intellectual property -- the name of the Palm and its memorabilia. Fresen, Oliver's attorney, says he wants any plans to include Oliver. He'd like to see her stay on as co-manager or consultant. Or turn the Palm into a museum. "It's moot now," Tillman says. "The fact of the matter is 47th Street is going to be developed." Oliver sees value in what was. Tillman sees value in what will be. "It's all about money in this world," Oliver says, resigned yet rebellious. To make her point, she reaches into the old-fashioned cash register behind the bar and pulls out a handful of bills. Special correspondent Kari Lydersen contributed to this article. © 2001 The Washington Post Company