Last Stand on 47th Street: Gerri's Palm Tavern Fights for Its Life

By Kari Lydersen

StreetWise, Chicago, IL

May 21 - 27, 2001

Vol. 9, No. 30

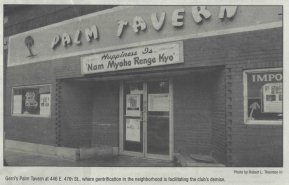

A tattered storefront on a run-down section of 47th Street, bearing a peeling sign with green wooden palm trees and letters and some neon beer signs in the small windows, Gerri's Palm Tavern looks inconspicuous enough.

But walking inside, it is obvious that this unassuming tavern is a piece of Chicago history. In fact, the history of Bronzeville, the south side area which was the destination of many poor Blacks coming north during the Great Migration as well as home to many wealthy blacks during the 1920s, 30s, 40s and 50s, wouldn't be complete without Gerri's.

The Palm Tavern was founded in 1933 by James "Genial Jim" Knight, one of the "policy barons" who built Bronzeville as an affluent, vibrant African-American community largely on the strength of the "numbers game," a form of gambling which was later made illegal and taken over by the government in the form of the lottery. The Chicago Defender, the country's only black-owned daily paper, called the tavern "the most high classed Negro establishment in America" at one time.

Gerri Oliver, now 82, was born in Jackson, Mississippi, the great granddaughter of a slave, and came north in the 1940s to study the mortuary business, the family business she had been a part of in the south. "I used to go to my uncles to pick up the bodies," she said. "He'd have the bodies stacked along the wall in baskets. The man with one million dollars could be at the bottom of the basket and the man with nothing on top. It didn't matter once they were all dead."

In Chicago, Oliver worked at the Western Electric company, where she said she "was one of the first women to break the color barrier," and then became a manicurist. She met Knight while doing his nails. In 1956, he sold the tavern to Oliver.

"Gerri was one of the only African-American women in the city to own a business at that time," said Gary Fresen, Oliver's attorney. "This was said to be one of the first places that got a liquor license after prohibition. Gerri's is the real thing. This is an amazing part of the city's history and the history of the whole country."

Oliver served home-cooked meals about once a week at the tavern, which became a haven for some of the world's most legendary Black jazz and blues musicians, community leaders, politicians and authors. Regulars included Josephine Baker, Muddy Waters, Dizzy Gillespie, Jesse Jackson and young Jesse Jackson Jr., Langston Hughes and countless others. A wall of fame on one side of the bar bears wooden plaques with the names of many of these luminaries. Photos hung throughout the bar show a young, pert Oliver with entertainment and political stars. Most of the artifacts and fixtures in the tavern are still the originals from the 1930s or 1940s. The art deco bar remains, adorned with a garland of leaves.

"I'm a florist by training," Oliver says.

Behind the stage are a Gerri's Palm Tavern neon sign, and a handful of booths and tables crowd the relatively small club. Paper balls, garlands and balloons adorn the walls, and old sports trophies, photos, beer signs and other artifacts decorate the top of the liquor cabinet. The murals lining one side of the tavern, once bright scenes of palm trees and water, are now covered in a reddish brown haze from decades of cigar smoke and sweat. Fresen notes that the murals could be restored to their original glory but it would take thousands of dollars.

Overall, there is an air of tarnished glory to the place, a musky scent that belies years of artistic brilliance and also hints at the current vital role the tavern plays in the community. On a typical afternoon, a handful of friends, supporters and patrons trickle in and out to talk to Gerri and sip an afternoon beer.

This is how Gerri's has been for years. But there is an air of urgency and sadness in the tavern these days. Since the city initiated eminent domain proceedings to seize the tavern from the owner and evict Oliver a year and a half ago, the taverns days have been numbered. Oliver rents on a month to month lease, giving her no security in the building. An ongoing effort to save the tavern has kicked into high gear in the past few months, as supporters have become more and more vocal about the importance of Gerri's and the urgency of its plight.

Oliver said she got the letter informing her of the eminent domain proceedings just days after getting a letter from Mayor Richard Daley naming Feb. 13, 2000 "Gerri Oliver Day." She notes that the Gerri Oliver Day proceedings were launched by The Chicago Defender.

Jennifer Hoyle, spokesperson for the city's law department, said that the city seized the building because the owner, David Gray and Midwest Partners, has not kept it up to code and it is dangerous for patrons to go there. She also said that Oliver has been sleeping there, which violates code and is also dangerous given the condition of the building. Fresen agrees that the building is in bad shape due to the fact that the owner, which he calls a "slumlord," has done almost no upkeep on it since buying it in a tax sale in 1989 for $8,000. Gray did not return calls for this story.

Hoyle said that the city has purchased the building from Gray, and plans for it are still unclear. As is usually the case in situations like this, Oliver and her many supporters see a lot more than concern about safety behind the city's purchase of the building. For at least a decade, Third Ward Ald. Dorothy Tillman, whose offices are around the corner from the tavern, has had a plan to renovate 47th Street as an "African village" and blues heritage district. As part of this plan, the 47th Street Cultural Center and Lou Rawls Theatre is being constructed on the corner of 47th Street and King Drive, across the street from the tavern. The 47th Street plan has been controversial and plagued by financial and planning difficulties from the start, with many charging that it is a "Disneyfication" of the area meant to appeal to tourists and people from outside the community while failing to preserve or respect the actual history of the area.

The city has sold another lot it had seized, on the northwest corner of King Drive and 47th Street, to the Second City comedy club for a token one dollar. It has also earmarked $800,000 in federal Empowerment Zone funding for Second City. Many say this is a gross diversion of funds meant to help the existing community.

Harold Lucas, president of the Black Metropolis Convention and Tourism Council, is one of the high-profile critics of the 47th Street plan. He objects to the labeling of the area as "Tobacco Road," a reference to a Lou Rawls' song about Black migrants coming up from the south.

"That's an insult," he said of the moniker. "There's a hidden history here they don't want us to know. This was actually a very wealthy area built on the numbers racket. Gerri's is a byproduct of that. And Gerri's goal is to pass that legacy on to another generation."

Oliver's supporters say that it is ludicrous that the one authentic piece of 47th Street history left, the tavern, is being destroyed, while the city is pouring millions into "recreating" the area.

"They're trying to impose a revisionist history on the African-American community," said Lucas. "They're trying to destroy what existed. Why would you give Second City a lot for one dollar and $800,000, and not give Gerri a dime?"

Lucas sees the 47th Street project and Oliver's eviction as part of a larger trend of gentrification in the area.

"Its all about land," he said. "This is prime lakefront property. They claim to be empowering low-income people, but actually they're gentrifying low-income people out. People are already being pushed out. Its racism." Lucas owned the Supreme Life Building at 31st and King Drive, just two miles south of Gerri's, and planned to turn it into a visitor information center for the area until the city seized it through eminent domain in March. The same judge proceeded over that process as is proceeding over the Palm Tavern. "Anything that is owned and controlled by the African-American community, they're going in and trying to take it," he said.

Oliver's supporters say she has an application for Empowerment Zone funding of her own prepared. Hoyle said she has not heard of such an application. "What you need to look at is the corruption of the Empowerment Zone in Chicago," said historian Nathan Thompson, who has written a book about the history of Bronzeville. "This is money that was supposed to go to the community. Second City has nothing to do with this community."

Hoyle said Oliver would likely not be sold the Palm Tavern building for one dollar, as supporters are hoping. She said the building likely wouldn't be demolished, but would be incorporated into the historic district in some way. "This building needs a lot of work to get up to code," she said. "Gerri Oliver doesn't have the money shed need to do the rehabs on her own." Hoyle said the tavern could be moved to another location, and she said the city has agreed to provide security once Oliver is evicted to make sure the historic fixtures aren't disturbed. She also said the city would assist Oliver in finding affordable housing. Oliver said she feels the city wants to keep the tavern there, but with someone younger manning it.

"They want me out," she said.

The campaign to save the tavern, which includes support around the U.S. and even in other countries, includes countless letters sent to the Mayor and Tillman and ongoing protests outside the tavern and at Tillman's office. Tillman, who has spoken to the media little about the affair, failed to respond to calls for this story. While Oliver says she doesn't want to talk about Tillman or get involved in the politics of the issue, Fresen and other supporters say Tillman is directly responsible for the plan to seize the tavern.

"This wouldn't be happening without her," he said. He is one of several who credit Oliver with "making" Tillman, helping her gain her position as alderman by marshalling community support.

Paula Robinson, managing director of the Bronzeville Community Development Partnership, said Oliver may have gained the animosity of Tillman over the years. She noted that Oliver once held a party for former police officer Pat Hill, who campaigned against Tillman in an aldermanic election.

"The alderman has refused to talk to the media and she has refused to meet with constituents about this," she said. "But Gerri has been a constituent of this area for 45 years."

Many supporters are hoping the Palm Tavern will be allowed to stay and become part of the revitalization of the area. Robinson noted that it only makes sense that the tavern would be a financially lucrative as well as important part of the historical district.

"For international tourists in particular, the number one thing they want to see is jazz and blues, and they want to see it in an authentic setting," she said. "There is cultural tourism, which you can get at the cultural center downtown, and then there is heritage tourism, which is something you experience in an authentic setting. Its about ownership and culture. As a whole, the Black community has not been successful in owning and controlling its culture. We have to reclaim some of this. Were not going to go away. We think Gerri will become the poster child for 47th Street."

"This is really the will of a small group of people who stand to gain financially versus the interests of people all over the world who want to see it stay," said Bernard Turner, president of the Bronzeville/ Black Chicagoan Historical Society. "There's no reason to close it down. We think that with the increased exposure and enough people complaining, she will get to stay." But Oliver seems cynical about her chances of keeping the tavern on 47th Street.

"Its all about money in this world," said Oliver, pulling out a handful of bills from the old-fashioned cash register to make her point. "They want to put a value on your accomplishments. From my perspective, value is about passing on what I've learned to others."