"Historic Bar's Future Up for Grabs"

By Kate Zambreno

Network Chicago's CityTalk

May 18, 2001

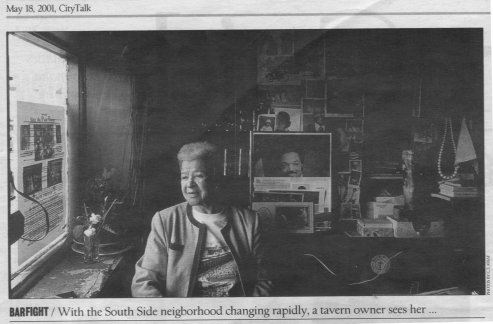

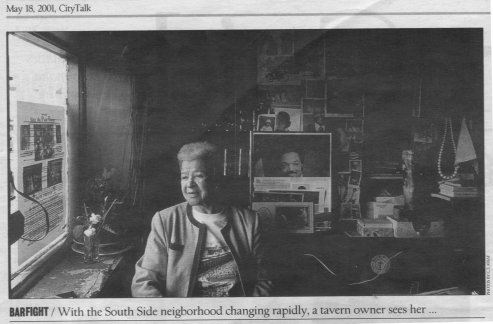

Gerri Oliver, 82, sits at her place by the window of Gerri's Palm Tavern, watching 47th Street go by. Except lately, there hasn't been much to look at, just vacant lots and remnants of yesterday.

If she turned her head she could see on the comer the sparkling new 47th Street Theater and Cultural Center, recently resurrected on the site of the old Regal Theater. But "Mama Gerri," as she's been called for the 45 years she's owned this legendary joint at 446 E. 47th St., looks straight ahead.

"Every day is a come day, go day, and I'm going to be here until the headline's printed on the wall," she had just told veteran 1V reporter Harry Porterfield. It was one of many interviews Gerri has given recently in a passionate campaign led by community supporters to save the decaying tavern.

But now Gerri looks a little tired. Perhaps she is thinking back to the golden days, when the area around 47th Street and South Parkway -- later renamed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive -- was the main ventricle pulsating through the black metropolis that was Bronzeville, rich and alive with excitement. When folks would get dressed up to the nines to go see jazz greats like Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie play at the Regal, and then crowd into the Palm Tavern afterward to see and be seen. Count Basie, Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, Quincy Jones, Miles Davis, Langston Hughes, Jesse Jackson and Josephine Baker all hung out at the Palm. And if they were lucky, they were treated to a meal of Mama Gerri's famous red beans and rice.

The Palm Tavern of the past lives on in Gerri's memories. Like when Harold Washington became Chicago's first African-American mayor in 1983, and the Palm served as the campaign hub and later the spot for exuberant celebration.

Historian Timuel Black travels back much further, to 1937, before Gerri was owner, when Joe Louis won the world heavyweight championship and afterward everyone went to the Palm Tavern.

"Let's go to the Palm, we said," he remembers. "Outside was just full of people. There was nothing except joy. Because symbolically it indicated for many of us young blacks a ray of hope." It's a story Black still holds onto. "I could take my children when they were children up 47th Street, and stand outside the Palm Tavern, and tell them that story." But starting in the late '60s the population of Bronzeville changed.

Public housing went up, and with that came gangs and drugs. One of the only links connecting the golden past and the Bronzeville of today is Gerri's tarnished tavern, which makes up with soul what it lacks in luster. It still fills up on weekends with young talent, and the musical I Was There When the Blues Was Hot has played there for three years. But patrons don't line up around the block like they used to, and much of the time, Gem is the only soul inside.

The tavern's interior is a darkly lit shrine, art deco bar and stools still intact, the vinyl booths duct-taped from years of wear, the splashy tropical mural faded, the roof damaged from a fire.

Dusty glasses line up next to medicine bottles at the old cluttered wooden bar, spilling over with junk and priceless trinkets. Photos are taped up everywhere. A hairdryer is plugged in. A soap opera provides the background noise. What many don't know is that Gem has lived at the Palm Tavern for eight years, on a mattress in a small back room.

The only thing new is a glass case by the door, filled with tourist memorabilia, crisp white T-shirts for $15 and pamphlets from the Chicago's Neighborhood Tours Program, where the tavern is a highlighted stop.

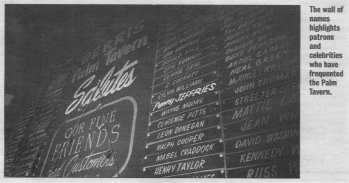

History is on the walls at the Palm Tavern. There's the wall of names of friends and famous patrons, and fading portraits of everyone from Sarah Vaughan to jazz singer Dakota Staton to Dizzy Gillespie to Harold Washington to James Knight, the policy king and first "Mayor of Bronzeville, " who opened the tavern in 1933. One portrait by the stage is of a saucy young Gerri, daintily leaning her arm against the wall.

Cats prowl around on the bar, where thick scrapbooks are spread out, filled with newspaper clippings, black-and-white photos from the heyday, as well as more recent ones, like Gerri posing with Mayor Daley last February, when he proclaimed her a "cultural icon" for not giving up on 47th Street.

But a cloud of uncertainty connects the past and the future. Alderman Dorothy Tillman has had multimillion dollar plans in the works for years to polish up the strip in her Third Ward by turning 47th Street into an African Village and a blues nightclub district under her not -for-profit organization Tobacco Road Incorporated. The Cultural Center is already up, with a new Second City theater being built and plans in the works for a Quincy Jones plaza, as well as an African Bazaar with themed restaurants and shops.

But there are no plans yet for Gerri's. The city is involved in a lengthy legal process of rescuing the dilapidated building from its landlord through eminent domain. Gerri doesn't own the building, which is why it's never been renovated.

There's no word yet from Tillman about whether there's room for the Palm Tavern in her Tobacco Road. Bronzeville preservationists are upset with Tillman because of the historical inaccuracy of her project, and because it ignores the tavern, which they call the last landmark on 47th Street. No plan is a bad plan, they say.

"We do not accept our elected officials trying to give us a Disney-like version about what the history of Bronzeville was like," says historical preservationist Harold Lucas, who, along with others, grew up in the area and is campaigning to save the Palm Tavern.

"Tobacco Road" is a reference to the book, movie and song about struggling in the rural South, which those who remember say is the furthest thing from what the upscale 47th Street was.

"It never was a Tobacco Road. It never was an African Village," says Black. And it was a jazz street, if there was music to be heard."

"You can't come in and cherry pick someone else's history," says Paula Robinson of Bronzeville Community Development Robinson says development groups have been interested in buying the Palm Tavern, but without the support of the Alderman, it's impossible.

Tillman could not be reached for comment, but Becky Carroll of the Planning Department defends the city's intentions, saying that they are in Gerri's best interest

"No one wants to recognize that Gerri is living in very uninhabitable conditions," she says, pointing to facilities that are not up to residential codes, the caved-in roof and an unstable back wall. "I can guarantee you that if the roof suddenly caved in, and Gerri was harmed, as well as the merchandise and the goods in her tavern, the city would be the first one folks would blame." Carroll says that a city representative has been working with Gerri for several months to find her; a new home in the area, with the city paying the rent for three years, as well as relocation and storage costs for the 1930s interior and fixtures inside and the valuable memorabilia.

Tillman and the City Planning Department plan to reuse the building for entertainment, Carroll says. But it ultimately depends on whether the building is salvageable and the cost to rehab it, which she predicts will be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But many say you can't put a price on Gerri's Palm Tavern.

"Landmarks are our memory," says Robinson. "When they take away your memory, you can be told anything."