"On the Beat"

By Jason Koransky

Down Beat Magazine

March 2001

"I'm a pack rat, I keep everything," proclaims Gerri Oliver as she emerges from behind her bar with a copy of the Chicago music magazine Musically Speaking, dated October 1959. "Look through this."

I start flipping through the pages, and get to a photo of Lena Horne. "She used to sit at this bar and start singing," Gerri, now 81, reminisces. "Keep on going."

I reach a page of reviews that has photos of Count Basie, Sammy Davis Jr. and Jackie Wilson. "Jackie used to come in here, throw a $1,000 bill on the bar, and say, 'Gerri, close the door and lock it I'm paying for everything that comes across that bar tonight.' "

On the next page sits a photo of Miles Davis. "Did he come in here too?" I ask.

Gerri lets out an incredulous sigh and has a little laugh. "Of course. Everybody came in here. They had no place else to go."

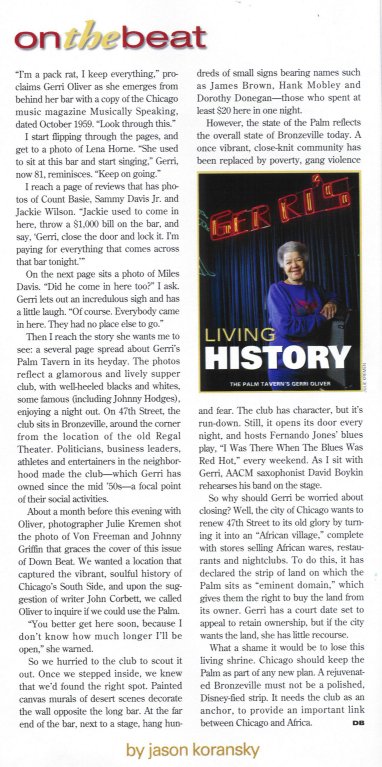

Then I reach the story she wants me to see: a several page spread about Gerri's Palm Tavern in its heyday. The photos reflect a glamorous and lively supper club, with well-heeled blacks and whites, some famous (including Johnny Hodges), enjoying a night out. On 47th Street, the club sits in Bronzeville, around the comer from the location of the old Regal Theater. Politicians, business leaders, athletes and entertainers in the neighborhood made the club -- which Gerri has owned since the mid '50s -- a focal point of their social activities.

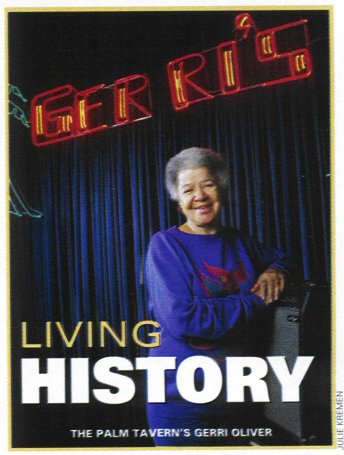

About a month before this evening with Oliver, photographer Julie Kremen shot the photo of Von Freeman and Johnny Griffin that graces the cover of this issue of Down Beat. We wanted a location that captured the vibrant, soulful history of Chicago's South Side, and upon the suggestion of writer John Corbett, we called Oliver to inquire if we could use the Palm.

"You better get here soon, because I don't know how much longer I'll be open," she warned.

So we hurried to the club to scout it out Once we stepped inside, we knew that we'd found the right spot. Painted canvas murals of desert scenes decorate the wall opposite the long bar. At the far end of the bar, next to a stage, hang hundreds of small signs bearing names such as James Brown, Hank Mobley and Dorothy Donegan - those who spent at least $20 here in one night.

However, the state of the Palm reflects the overall state of Bronzeville today. A once vibrant, close-knit community has been replaced by poverty, gang violence and fear. The club has character, but it's run-down. Still, it opens its door every night, and hosts Fernando Jones' blues play, "I Was There When The Blues Was Red Hot," every weekend. As I sit with Gerri, AACM saxophonist David Boykin rehearses his band on the stage.

So why should Gerri be worried about closing? Well, the city of Chicago wants to renew 47th Street to its old glory by turning it into an "African village," complete with stores selling African wares, restaurants and nightclubs. To do this, it has declared the strip of land on which the Palm sits as "eminent domain," which gives them the right to buy the land from its owner. Gerri has a court date set to appeal to retain ownership, but if the city wants the land, she has little recourse.

What a shame it would be to lose this living shrine. Chicago should keep the Palm as part of any new plan. A rejuvenated Bronzeville must not be a polished, Disney-fied strip. It needs the club as an anchor, to provide an important link between Chicago and Africa.