Palm Holds Both History And Her Story

By Dawn Turner Trice, Tribune Staff Writer

February 18, 2001

Chicago Tribune

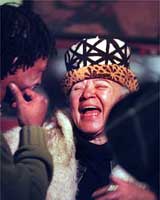

No bigger than a minute, Gerri Oliver walks down 47th Street toward Gerri's Palm Tavern with the air of a dignitary, head held high, shoulders square.

Some kids wave and yell out, "Hey, Mama Gerri."

The 81-year-old, wearing her trademark black leather coat and pink-and-white gym shoes, sings back, "Hey baby, how you do?"

Oliver has owned the Palm Tavern, one of the South Side's most famous and well-respected saloons, since 1956, and has established herself as a cultural icon and celebrity in the community.

These days Oliver looks down her street and worries. She wonders whether 47th Street's rebirth -- led by the $5 million Lou Rawls Theater and Cultural Center under construction at 47th and King Drive -- will mean the decaying Palm Tavern and all its history will have to move on, and her with it.

As she walks "to and fro," few people know that at the end of the day, she locks the tavern's doors from the inside and retires to a bleak room in the back, formerly the kitchen, where she sleeps on a mattress on the floor.

Her tavern, which once catered to such jazz greats as Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie but now rarely has customers, occupies rented space in a dilapidated, fire-torn building that also is home to a used furniture store. The city wants to acquire the building because it has fallen into such disrepair.

Despite petitions to save the tavern, Becky Carroll, a spokeswoman with the city's Planning Department, said officials are unsure what will come of the business.

To pass through the glass doors and into the cavernous main room of the Palm Tavern is to enter a bygone era -- an old wooden bar, cracked vinyl booths, and a Michelob wall clock on which time has stood still for two decades. There are photographs of jazz greats and trinkets that offer a glimpse into the black experience, from politics to civil rights. And there's evidence of Oliver's personal struggles.

"We were here when blacks couldn't go nowhere else to relax and put their feet up," said Oliver, standing behind the bar, wiping down the counter. "We were here when there was a spit shine on this street and (commerce was booming). And we stayed here when that shine wore thin and nothing was left but the spit."

Chicago historian Timuel Black recalls that as a boy, he would stand in front of the Palm Tavern, watching as limousines pulled up and such jazz legends as Ellington, Count Basie, and Louis Armstrong passed through the tavern's doors.

"The Palm was an upscale place that encouraged people despite the difficulties that accompanied race and class," said Black, 82. "It's hard to look at a vacant lot or into some converted space and tell your child, 'That's where the Palm used to be.' For that reason, it's worthy of being renovated and preserved."

Though Oliver rarely talks much about it, in recent years she has fallen on hard times. Oliver, who's divorced and has a son living in California, says she lost a nearby apartment to "swindlers a few years back," so she moved into the tavern.

For the past two months, the heat in the building has been iffy. She sits dressed in layers of coats and sweaters, bleeding radiators, trying to coax heat from them and from space heaters.

"I'm not a crybaby," she said one afternoon as she examined the dirt under her fingernails. She had spent the previous night "dipping water" from a leaky radiator in the men's bathroom. "Long ago, I gave up on believing life was going to get easier just because I got older."

Oliver doesn't recall dates anymore ("Every day is come day, go day," she said.). But she does remember that it was in the late 1930s when she left the relative security of Jackson, Miss., with her husband and young son. In Jackson, her family had owned a funeral home and hospital and had carved out as "good a life as blacks could back then in the South."

In Chicago, she had planned to take up a trade, mastering floral design or embalming techniques. But neither was "too stimulating" and after a series of jobs, she landed one as a manicurist where she met Bronzeville businessman and policy king James "Genial Jim" Knight, who sold her the tavern.

"I was a good Catholic girl," said Oliver, now a Buddhist. "I hadn't planned on buying no place like this. I had never stepped foot in here until I owned it. But I thought it was a challenge, so I did it."

Soon, bandleaders coming to Chicago to play at the nearby Regal Theatre, which was demolished in 1973, would call ahead, asking her to stir up a pot of her famous red beans and rice. Oliver said the musicians knew the Palm Tavern had a reputation for nurturing talent, young and old, while offering a decent place to eat and socialize.

"They came here because they were tired of eating out of brown paper bags, (while sitting) in the back of buses," she said. "You could be the biggest star on stage, but once you stepped off, you were still just another" black person.

She said being a female owner of a saloon was difficult, but her patrons respected her.

"Mind you, everybody thought I messed around, but I sure as hell didn't," said Oliver, who still fusses and cusses with abandon. "They gave me my due, because I wasn't afraid to speak my mind and I spoke it loudly."

She said learning Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. died in 1968 was one of her saddest memories. She closed the tavern and she and three barmaids flew to the Atlanta church of civil rights leader Rev. Ralph Abernathy, where volunteers answered telephone calls regarding King's funeral arrangements.

One of the happiest moments: when Harold Washington won the mayoral election in 1983, becoming the city's first African-American mayor. During the campaign, the tavern was a political hub, helping to get out the vote.

"We solicited votes from everywhere," Oliver said. "We even had children going door to door. "

She said when Washington was elected, "everybody loved everybody that night. It was like when Joe Louis won the (heavyweight) championship of the world. Sins were forgiven, if only for that one night."

The Palm Tavern doesn't do a lot of heavy politicking anymore, and the line of customers that once snaked around the corner is long gone. But the tavern continues to nurture talent.

The musical drama, "I Was There When the Blues Was Red Hot," has been playing there for three years and has reminded patrons that the Palm Tavern, though lacking in luster, still has a lot of character.

When Oliver crosses the alley to visit Otha's Grocery Store, in a building of equally uncertain fate, she walks with her back straight and her head held high. She has the grace of one wearing high heels, rather than the sneakers that help her manage the snow.

"Whatever happens, I have no regrets, none whatsoever," she said. "All my sisters and brothers have retired from good jobs and they're now resting on their laurels. Me? I'm still out here in the mix."